SCIENCE TO ART

(see original post at

http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2012/04/18/science-to-art/)

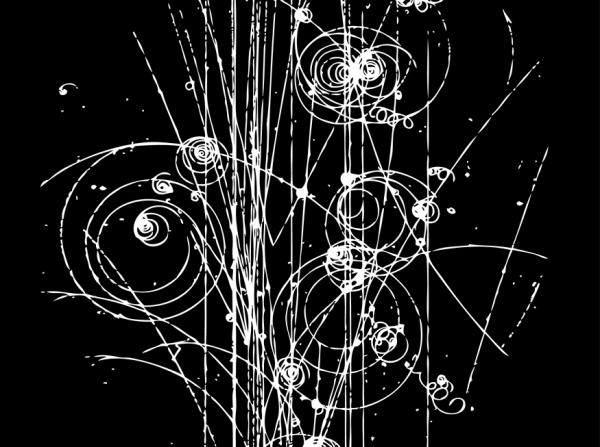

(above) Computer enhanced photo of sub-atomic particle collision in a linear accelerator’s ‘bubble chamber’.

The interplay between science and art is fascinating but ill-defined. Does science produce a kind of art almost incidentally, for example the images of sub-atomic particles colliding in a linear accelerator? They certainly look like art—abstract and evocative. But doesn’t a work of art have to be created with an intention to be so? If not, then any interesting image would be art and that would disturb the existing social system of values that insists that art be created by artists and science by scientists.

Not to digress too far into such questions, but several times in the last century this system has been challenged by artists themselves. Most notably, the Futurists proclaimed the cacaphony of factories and of the noisy machines inhabiting the streets to be the truest forms of modern music. The Dadaists likewise proclaimed ordinary objects like urinals and hat racks to be sculptures, which they called “readymades.” These and other similar redefinitions of art were based on a belief that the modern age was grounded in the commonplace and the everyday, and not in the narrow, over-cultivated tastes of a social elite. Together with this was the belief—or the hope—that machine technology and industrial mass production were liberators of humankind, and were creating a great new phase of human history, which needed its unique artistic expressions.

Meanwhile, back in the science laboratory, say, a very particular one called the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a giant machine under the border of France and Switzerland built to hurl protons at each other at extreme velocities, producing collisions that reveal the very smallest and highest energy sub-atomic particles. scientists study computer imagery to interpret, or understand, the most fundamental realities of the physical world. From that understanding new technologies will emerge, by which we humans will interact with the natural world and, so to speak, with ourselves. The LHC is, in short, an important source of new knowledge and will have a significant place in our history and—to the extent that we influence our world—the history of the planet.

My point here concerns the role of imagery in the creation of knowledge. The imagery of the LHC is computer generated: largely, arrays of numbers. The patterns recurring in these arrays are mathematical, in that they can be converted to algebraic expressions, and at the same time visual, in that their structure can be converted to logical expressions, much as, say, a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci. These ‘critical’ expressions are primarily verbal and, being in a common mode, contribute to shaping our cultural values.

However, apart from the direct output of the LHC, which can only be interpreted by specialists, the physical presence of the machine is expressive. The underground spaces it occupies, the tectonics of the machine itself, the iconic impact of its geometry, each and all are part of an aesthetic that is as much a part of our visual, hence cultural, sensibility as the streamlining of airplanes and the uniformity of mass-production was to an earlier generation. Visual artists such as Jonathan Feldschuh, whose paintings appear below, are interpreting in the traditional art media the very untraditional world of the LHC in order to give all of us access to it. His paintings combine the literal and the abstract, the representational and the symbolic in a needed synthesis of the known and the as-yet-unknown, or even the ultimately unknowable realities that lure us on.

Lebbeus Woods, April 2012

|

Read all available reviews: |

|