|

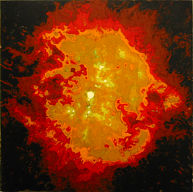

tema celeste, 92 (july/august 2002), p 89. jonathan feldschuh Cynthia Broan Gallery New York There was something touchingly ambitious about Macrocosm, Jonathan Feldschuh's recent exhibition of paintings. Attempting to bridge the chasm between science and art, the artist based his latest works on such big-brain themes as interstellar radiation and NASA's Cosmic Orbital Background Explorer (COBE). While colorful, the paintings revealed the weakness of many efforts to translate science into visual terms, failing to advance our appreciation of scientific knowledge or the possibilities of art. Almost certainly, the struggle to depict our science-based society will increasingly bedevil artists. How, for example, can art address such nonvisual phenomena as the Big Bang theory, cosmological chaos, or information theories? Feldschuh's solution was to use computer images provided by such orbiting instruments as COBE or the Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) satellite, applying swirling bands of acrylic paint highlighted with colored pencils and sealed in clear acrylic. His 2001 Universe (DIRBE 100 micron data), for example, visually renders the light of the universe as detected by COBE; Solar Flares (Trace Data) #1 (2002) portrays ultraviolet light readings from the sun recorded by TRACE. Without a doubt these paintings contain much beauty—the artist, who studied physics at Harvard University, is also a top-notch colorist. But his mastery of the color wheel only partially disguised a phenomenological issue underlying many of these works: They are not depictions of the cosmos, but rather of how machines record the cosmos, and as such they are reminiscent of superbly crafted scientific illustrations one might see at the Museum of Natural History. Feldschuh seemed to intuit this problem, for Macrocosm also contained works based on photographs of such empirical phenomena as the so-called Whirlpool Galaxy taken by the Hubble telescope and a hurricane shot by an orbiting NASA astronaut. Yet while these paintings displayed superlative color sense and deft pencil work, they seemed pale in comparison to actual Hubble photographs that ran on the front page of the New York Times the week Macrocosm opened. Feldschuh's effort to bring the right and left sides of the brain together was intriguing, but the two need more to say to each other. Steven Vincent

|

Jonathan Feldschuh. Nebula MI-67, 2001, Acrylic on canvas over panel, 91.4 x 91.4cm. |

|

Read all available reviews: |

|